America’s journalists, relentlessly attacked by President Trump, are also taking a beating in public opinion. However, their information-gathering cousins, librarians, are riding a cloud of popularity.

Is there something journalists can learn from librarians?

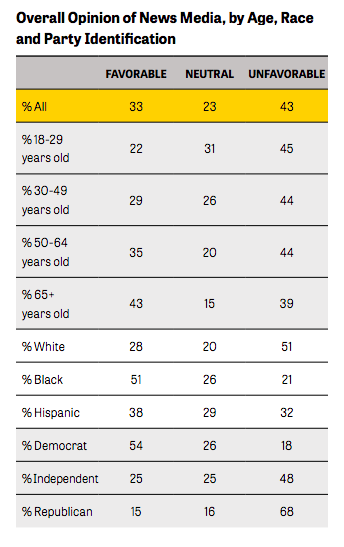

The Knight Foundation and Gallup gave the latest bad news to journalists on Wednesday, weighing in a mammoth poll showing only 33 percent of Americans have a positive view of the news media. Of 18- to 29-year-olds polled, only 22 percent trust the media.

By huge majorities, Americans see major problems with:

- Owners of news outlets attempting to influence the ways stories are reported.

- News organizations being too dramatic or too sensational in order to attract more readers or viewers.

- Too much bias in the reporting of news stories that are supposed to be objective (only 44 percent can think of a news source that they believe reports the news objectively).

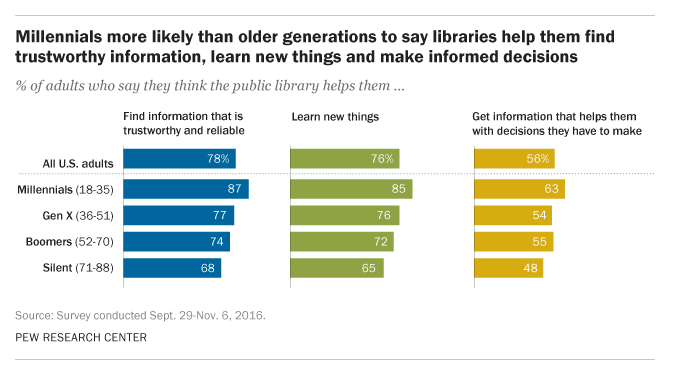

Contrast that with a Pew Research poll in August, in which 78 percent of Americans feel that public libraries help them find information that is trustworthy and reliable. Among 18- to 35-year-olds, that trust jumps to 87 percent, with 85 percent of Millennials saying librarians help them learn new things. Overall, 65 percent of U.S. adults say libraries help them grow as people.

The divergence in trust comes as some libraries have begun filling in the gaps left behind by shrinking traditional media, or gingerly taking over primary duties in areas abandoned by news outlets.

What explains the divide? Marilyn Johnson, author of “This Book Is Overdue: How Librarians and Cybrarians Can Save Us All,” says librarians have a head start. “Their mission is not to exploit us or make money off us, so they’re ahead of the game right out of the gate,” she says.

At a time when journalists are encouraged to engage with the community, librarians have been doing that for years. In addition to their day jobs, Johnson says, librarians help citizens find tax forms, navigate benefits, build resumes and complete job applications. One librarian helped Johnson learn how to incorporate.

Americans have been conditioned since they were kids to trust libraries and librarians, says Laura Saunders, an associate professor in library science at Simmons College.

“Kids who were taken to the library from a young age, who enjoyed story hour and remember getting their own library cards and borrowing their own books, will have positive associations,” Saunders says. At the same time, Americans “are hearing lots of criticism of news and media outlets, which again can color their thinking on those outlets as sources of information.”

Another advantage of librarians: Hosting GED and ESL classes, community circle meet-ups and providing temporary shelter for the homeless. These acts help libraries build trust among marginalized groups. As part of their job, librarians “are taught to help people access and evaluate information, but not to judge people’s questions or motives, but rather to support their intellectual freedom,” Saunders says.

Journalists may be able to learn something that librarians themselves have been struggling with for years: How to quantify their value.

Journalists may be able to learn something that librarians themselves have been struggling with for years: How to quantify their value.

“Everybody loves libraries, that’s not a problem. Whether they value them, it’s another question. We’re perceived as free. You used to pay for news; now you get it online for free. You folks are feeling some of our pain,’’ says Mike Sullivan, who runs the public library in Weare, New Hampshire.

Sullivan knows both libraries and journalists have to do more outreach — and explanation. He has taken the lead in his community in publicizing events and reporting news as editor of a weekly town newspaper he began in March.

On the value question, his library has begun printing the acquisition cost of materials that card-holders check out. That way, citizens see how much they “saved” by using the library for books and DVDs, both for the current item and a total for the year. It’s much like a CVS receipt for savings-to-date; or, seen another way, what some Sunday newspapers have done with the value of the coupons in each edition.

But journalism’s value is much greater than coupons, and broadcasting a community’s distinctiveness is only part of the mission. Libraries cannot bring down a president, or regularly push accountability of government officials who may help fund the institution.

One thing news outlets should do is work more closely with libraries, says Tom Huang, who has done just that in spearheading several partnerships as assistant managing editor for features and community engagement at the Dallas Morning News.

In get-togethers or classes with librarians and patrons, journalists can show the work they do to provide accurate information. They could encourage patrons to follow them to a community meeting. The Morning News has helped train scores of high-schoolers on journalism techniques, Huang says.

Moving closer to librarians might enhance journalism’s standing as well.

In areas not served by traditional news outlets, libraries, already trusted by the community, could become a hub for news collection, Huang says. There would have to be training on one-on-one interviewing techniques or how to be an assigner or “editor” for events or stories done by community members — as well as the understanding that these are beginning steps to journalism, not involved investigative pieces.

“Ultimately, we could train librarians to do some of this stuff,” Huang says. “It’s not like it’s rocket science.”

—

Know of other library-journalism collaborations? Please email the author at beardwrites@gmail.com with examples.

Related:

Welcome to your local library, which also happens to be a newsroom

Its paper closed, one paper bounced back — with a librarian in charge